The Reshaping of Britain

Church and State since the 1960s

A Personal Reflection by Clifford Hill

Wilberforce Publications

Available from Amazon and CLC bookshops

Two reviews of a landmark book tracing Britain’s spiritual and social history from the 1960s onwards

“A real 21st century epistle that deserves reading and rereading”

I was glad to have the free time to read this ‘can’t put down’, riveting book because I have lived through the times Clifford Hill writes about and he accurately describes the spiritual and moral decline of the UK.

During my ministry as a vicar I was unable to make the people aware of the things he highlights. Clifford carefully supplies his material, often quoting his sources. He brings together with startling clarity his reflections on this terrible drift away from the Word of God and the darkness which is coming upon this land unless there is real, deep repentance.

He is careful in presenting any thoughts of revival and is wary of those who do.

There is much interesting material in this book which includes his contacts with spiritual and political persons in high office.

He is not part of the ‘establishment’, but his academic and pastoral work over many years qualifies him to express the opinions that he does.

The book sadly catalogues the many missed spiritual opportunities for preaching the Gospel to the nation and the lack of effective Christian leadership since the war, but thank God for this timely publication.

It is my prayer that it is acted upon by those in authority. It is well written and I believe this is a real 21st century epistle that deserves reading and rereading, because Clifford is a man of deep prayer with a faith based firmly on the Word of God.

‘The Reshaping of Britain’ is possibly the most important book written so far this century and must be taken seriously.

Rev Richard Miller

No punches pulled in this eye-opening account of a nation in decline

Someone less nice than Clifford Hill could have called his latest book, “I told you so.”

It is a significant legacy, tracing the slow-motion car crash of British morality since the Sixties along with the Church’s waning influence.

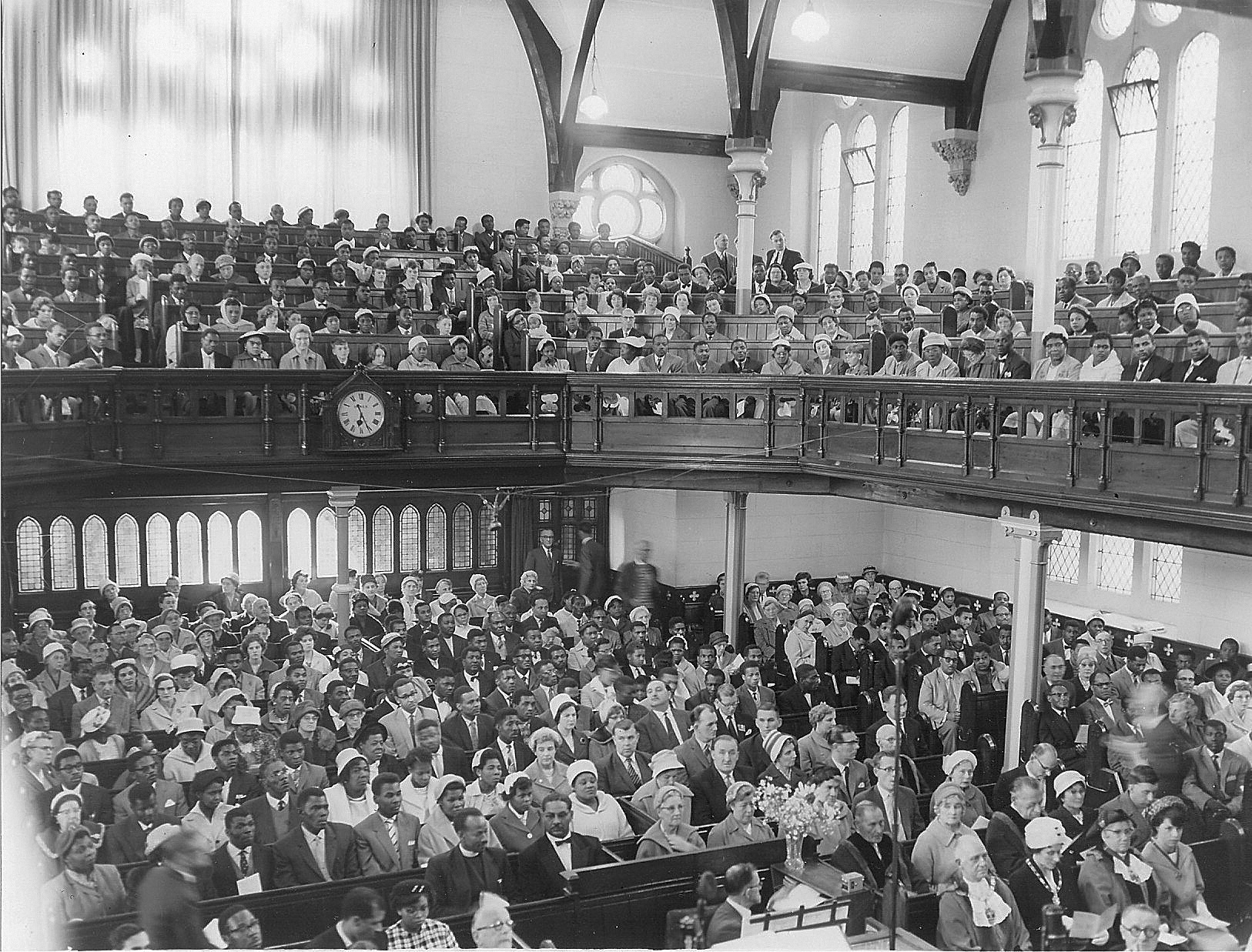

It is also an autobiography of sorts, but he gets personal details over with in the introduction. Once he and Monica were married, they became a true partnership, implicitly trusting the other as they worked together running churches and then seeing the birth of ‘Prophecy Today’, Clifford’s cutting edge magazine (which has been reborn as an online magazine) and Monica’s Church Growth Association.

All the decades of fruitful ministry continued despite the most staggering let-down by Anglican authorities in the first chapter. Running a highly productive community renewal programme in the East End, Clifford was courted by Lambeth Palace with the invitation to take the initiative nationwide. But church politics intervened and in order to maintain unity in the Church of England, liberal bishops were invited onto the ‘Lambeth Group’, with the result that after months of meetings and prayer, Clifford Hill was dropped from a role he’d never applied for.

“I crept back to the East End,” he writes. Decades later, one can feel the pain and disappointment: “Jesus wept over Jerusalem when the leaders failed to perceive the time of God’s coming among them,” he says. “I have no doubt that it was not only Archbishop Donald Coggan and Canon John Poulton and Monica and I who were weeping over Britain in 1978.”

Yet Clifford’s influence on national affairs did not end there, nor did he cut himself off from the C of E. Clifford was close to four Archbishops – whether or not they believed in God. Robert Runcie comes off worst; Clifford makes it clear that Archbishops Runcie and Habgood left a legacy of unbelief in the Church of England.

After the Lambeth let-down he was head-hunted by the Evangelical Alliance to do the same job under their banner, but watched the effects on national life as the liberal bishops (he makes it clear that ‘liberal’ is a pejorative term) succeeded in keeping the Church of England united, at the cost of a loss of influence in the nation which led to drastic social change.

Clifford does not pull his punches. He charts how the Church stood in the wings during “the most rapid and radical period of social change that the world has ever known – a process that is continuing to this present time.”

Nor does Clifford spare the charismatic movement of the 1990s. The much-heralded visit of the Kansas City Prophets comes in a chapter called ‘False Prophets’. Clifford was involved in trying to dissuade John Wimber from proclaiming revival and makes it clear that revival only comes out of brokenness, of which there was little around at the time.

As someone who was only a new churchgoer at the time, it is eye-opening to read what was going on behind the scenes of these much-hyped meetings.

Clifford’s tone, however, is, like the Bible’s, always measured. He is recounting what happened, like any historian, and ends on a note of hope, as a prophet should, because there is always hope with God.

Few could have allied the spiritual and sociological so clearly; for this alone Clifford Hill’s legacy should be cherished.

Melanie Symonds